James Brown was born to lose. He refused to accept that fate.

By the time he was in his 30s, James Brown was more than a dominant musical voice: he was an outstanding African-American personality, period. Important enough to be drawn into the murky waters of national politics as an inspiration and role model, he was also feared and sometimes ridiculed. But he would not be denied.

Nearly stillborn, then revived by an aunt in a country shack in the piney woods outside Barnwell, South Carolina, on May 3, 1933, Brown was determined to be Somebody. He called his group “Famous” before they had a right to; called himself “Mr. Dynamite” before his first Pop hit; and proclaimed himself “The Hardest Working Man in Show Business” before the music business knew his name. His was a fantasy, a sweet dream. But James Brown had singular talent, and the vision to hire the baddest. In his own time, he became “Soul Brother Number ONE,” a larger-than-life Godfather of Soul.

“JAMES BROWN is a concept, a vibration, a dance,” he told us recently. “It’s not me, the man. JAMES BROWN is a freedom I created for humanity.”

Some say it was a freedom too bold. Night after night, on stage and in the studio, his blood swirled, his legs split and his body shook. But talking to a crowd stretched at his feet in the late 1960s, James Brown reassured them: “If you ain’t got enough soul, let me know. I’ll loan you some! Huh! I got enough soul to burn.”

Music was an emotional charge for the young James Brown. Raised in a whorehouse in Augusta, Georgia. Brown never knew his parents’ love or guidance. His main concern was hustling; his main outlet was sports. He liked music: gospel when he attended church; big-band swing and early rhythm & blues that he heard that he heard on the radio and on jukeboxes, particularly the . Louis Jordan with his Tympany Five was a special inspiration.

In 1946, all of 13 years old, Brown first tried his musical luck with his Cremona Trio, a penny-making sideline. His career halted temporarily when he was imprisoned for petty theft in 1949.

Paroled in Toccoa, Georgia, in 1952, under the sponsorship of the local Byrd family, Brown started to make music his principal motive. Initially, he sang gospel with Sarah Byrd and the church club, then joined her brother Bobby Byrd’s locally established group, known as the Gospel Starlighters or the Avons, depending on what or where they performed.

There was no cohesive plan. Transporting illegal hootch across the state lines was a bigger moneymaker than their day jobs and night gigs. Gradually, though, singing rhythm & blues seemed to make the most sense.

“When we saw all the girls screaming for groups like Hank Ballard & the Midnighters, we thought, ‘Oh, so this is what we want to do!’” Bobby Byrd said. “We were versatile. I would do Joe Turner, Fred Pulliam did Lowell Fulson, Sylvester Keels would do Clyde McPhatter, and James would do Wynonie Harris and Roy Brown.”

Too poor to afford horns, “either James or I would whistle or we’d scat sing it together,” Byrd added. “Our voices always did go well together.”

The Avons did pop ballads, too, for the afternoon tea parties and such. But in clubs and high schools, Brown, having emerged as the group leader, was bit more reckless.

“The dancing y’all seen later on ain’t nothing to what he used to do back then,” Byrd said. “James could stand flat-footed and flip over into a split. He’d tumble, too, over and over like in gymnastics. We’d say, ‘What’s wrong with you? When it’s time to record, you’ll have killed yourself.’”

Managed Toccoa’s Barry Trimier, the group would gig in any convenient combination with assorted aliases. Events accelerated after they took the stage, unannounced, at a local show by Macon’s Little Richard.

Richard’s manager Clint Brantley was impressed enough to assume the group’s bookings. When Richard hit with “Tutti Fruitti” in 1955 and left Macon, Brantley had the group, now realigned and called themselves the Flames, fulfill Richard’s performing dates. James Brown saw his moment.

“I’ve never seen a man work so hard in my whole life,” Byrd recalled. “He’d go from what we rehearsed and leap off into something else. It was hard to keep up. He was all the time driving, driving, driving.

“This is when he really started hollering and screaming, and dancing fit to burst. He just had to outdo Richard. The fans started out screaming, ‘We want Richard!’ By the end they were always screaming for James Brown.”

By the fall of 1955 the Flames had worked up a furious, gospelized tune called “Please Please Please,” inspired by “Baby Please Don’t Go,” a blues standard that had been a substantial hit for The Orioles in 1952. Emboldened by the response to their shows—which featured not only the JB flip ‘n’ split but Brown crawling on his stomach from table to table—the group recorded a spare version of the song in the basement of Macon radio station WIBB.

“It was simple, just a guitar and the voices around one microphone,” said former disc jockey Hamp Swain, who was the first person to play the song on the air, at the competitor WBML. “Our audience liked it. At the time, though, we weren’t thinking this was the beginning of anything.”

It gave Ralph Bass the shivers. A talent scout and producer for King’s Federal label, an r&b pioneer who had overseen the recording careers of T-Bone Walker, Little Esther Phillips, the Dominoes many others, Bass heard the tune while visiting King’s Atlanta sales branch.

“I didn’t know who the group was, or the lead singer,” Bass said. “But I knew I had to have that song.”

While a violent rainstorm grounded Leonard Chess, head of Chess Records, in Chicago, Bass drove all night to Macon, where he encountered a curious local custom.

“Brantley didn’t want anyone else to know he was dealing with an out-of-town white cat, so I got instructions over the phone to go to the train station and watch the blinds of the barbershop across the street,” Bass said recalling his disbelief. “He told me that at eight o’clock, when the blinds go up and down, that would be the signal to go in. Sure enough, eight o’clock on the button, there went the blinds, and in I went.”

Bass got the Flames’ signatures on a King/Federal contract for two hundred dollars. He still didn’t know who the lead singer was until that night at a club outside of town. The screaming girls tipped him off.

Syd Nathan—irascible, cigar-chomping, myopic, business-savvy Syd Nathan—led King Records out of Cincinnati, Ohio. He had molded it into one of the U.S.’s leading independent labels, strong both in country and r&b, home to many of the Flames’ idols, including Bill Doggett, Roy Brown, Little Willie John, the “5” Royales and Hank Ballard. To the group—each of them poor, Southern, twenty-something—signing with King carried a lot of hope.

The Flames drove to Cincinnati for a session with the King house band on Saturday, February 4, 1956, recording in three hours “Please Please Please,” “I Feel That Old Feeling Coming On,” “I Don’t Know” and “Why Do You Do Me,” which sounded more like Charles Brown than James Brown.

Bass got what he wanted—a bigger better version of the “Please Please Please” demo. But boss Nathan hated the record, threatening to fire Bass and refusing to release it. Bass talked him out of doing both.

“I took a dub of the tune on the road with me,” Bass said. “Every chick I played it for went crazy. I told the old man to release it in Atlanta, test the waters, you know. He said he’d prove what a piece of shit it was by and putting it out nationwide.”

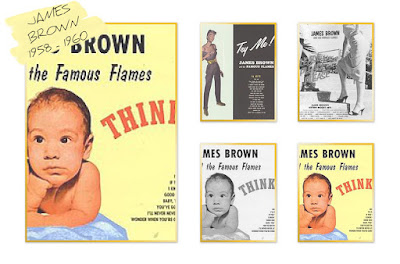

Bolstered by a strong live show and massive sales throughout the South. “Please Please Please” eventually reached the national R&B Chart Top Five. James Brown and the Flames were becoming Famous.

Or so they thought.

“Please Please Please,” though it eventually sold a million copies, was actually out of step with the times. With the rise of r&b reborn as rock ’n’ roll, and the skyrocketing careers of Little Richard, Fats Domino, the Platters and a young Elvis Presley, Nathan’s dislike for the song had some commercial validity. And while in the long run James Brown would lead the revolution, “Please Please Please” seemed doomed to forever mark him and the Flames a regional flicker.

For the next two-and-a-half years, Brown watched as every follow-up single—nine in all—failed. The other Flames, already distressed by Brown’s top billing, quit and went home; Nathan wished JB would go with them. But the fiery singer soldiered on in Southern obscurity, backed by keyboardist Lucas “Fats” Gonder from Little Richard’s band and whomever they could rustle up.

In the summer of 1958, Brown originated, adapted or was given a pop-gospel ballad that became his salvation. He recorded “Try Me”—a literal plea for acceptance—in New York on September 18, with a studio band that featured future jazz great Kenny Burrell on guitar. By January 1959, his record sat on top of the national R&B chart and snuck into the Pop Top 50.

Its success sparked the interest of a professional manager, Universal Attractions’ founding father Ben Bart, and the recruitment of a regular backing band led by tenor saxophonist J.C. Davis. It led to the return of ex-Famous Flame Bobby Byrd, who had been supervising Brown’s quality control at the King pressing plant and was also rewriting songs from Nathan’s publishing concerns. And it inspired King Records to be suddenly interested in its rough-hewn “hollerer,” releasing two full-length James Brown albums. “Try Me” had kicked off the countdown to Star Time.

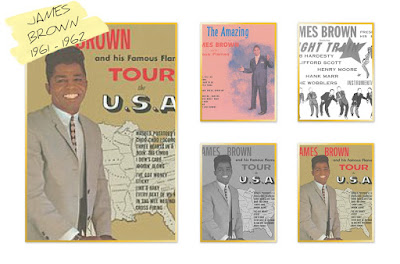

Two decent-selling singles followed, “I Want You So Bad” and “Good Good Lovin’.” Brown and band debuted at New York’s legendary Apollo Theater. But Brown’s next big hit had to come on the sly.

With his backing band firmly established as a healthy unit, Brown suggested to Nathan that they be given their own record releases. He had seen them do particularly well in featured spots on the road with numbers to which the kids could dance a new thing called the “Mashed Potatoes.” But after the flop of one James Brown instrumental on Federal—“Doodle Bug,” credited to “James Davis”—JB couldn’t get Nathan’s support. He turned to Henry Stone, an old Miami friend and independent record distributor who also ran his own small label, Dade.

“James was so upset with Syd Nathan,” Stone said, recalling the December 1959 session. “He and the band were doing ‘Mashed Potatoes’ on stage, and getting over, but nobody at King would listen. He came in, angry, he was gonna do the shouts himself. I kept telling him, ‘James, you can’t do this. You’re signed to another label and I do business with Nathan.’”

Stone overdubbed Miami DJ “King” Coleman on the lead vocal, although in the process Brown’s yelps remained audible. He billed the group Nat Kendrick & The Swans, after the drummer. “(Do The) Mashed Potatoes,” on Dade, became a R&B chart Top Ten and sparked a national craze.

Brown watched as “Mashed Potates” outran his own ”I’ll Go Crazy,” an exciting track despite his band’s apparent lethargy in the studio. Between takes, the frustrated leader urged them to dig deeper, saying, “Well, it’s a feelin’, you know. You got to have the feelin’.” They tried to get the feelin’ seven times. Like most of James Brown’s best records, the first take became the 45 single master.

As both songs were charting in February 1960, Brown revamped the “5” Royales’ “Think,” a 1950s harmony classic he dearly loved, into an early funk classic. He hurried during the session, forgetting the words on one take. His eventual final version, now recognized as a turning point in popular music, was arranged on the spot.

While Brown eventually had the confidence to direct his studio sessions, on early recordings he listened carefully to advice from King engineers and producers. Through several awkward takes of “Baby You’re Right,” Brown was apologetic for slowing down the session. Soothed and encouraged by studio personnel, JB soon belted the song’s dramatic opening with precision. His take evoked an exclamatory “That’s the way!” from the engineer.

Over the next two years, Brown’s biggest hits—“Bewildered,” “I Don’t Mind,” “Baby You’re Right,” “Lost Someone”—were ballads, less orchestrated than the smooth pop dominating the charts. He extended them into knock-down, drag-out performances in his stage revue, flourishing wildly colored capes while backed by the longest-running Famous Flames lineup: Bobby Byrd, Bobby Bennett and “Baby Lloyd” Stallworth. The show also included frenetic performances of the uptempo material he’d cut, like “Night Train.”

A sped-up “Night Train” was a top 40 smash; legend has it Brown played the drums on the hit version when regular drummer Nat Kendricks took a bathroom break. The track took four takes to get right; JB is on all of them, struggling with the rhythms until an unidentified producer or engineer offered advice. “James, don’t rush your drum beats so much,” he said. “Just give ’em a fraction more space.”

Behind or in front, JB had earned the title “Mr. Dynamite.” His vastly improved live shows, helmed by trumpeter Louis Hamlin, a Baltimore schoolteacher by trade, were kicking tail. A vice president of BMI, Charlie Feldman, recalled a dramatic summer afternoon seeing such a show at Rickwood Field in Birmingham, Alabama, home of the city’s minor-league Barons baseball team.

“Everyone had on their best clothes, because JAMES BROWN had come to town, in a three-quarter-ton truck right on the field,” Feldman said slowly, savoring the memory. “I remember one woman in particular in the first row of seats, wearing a new outfit, all her attention on James.

“When he went into ‘Please Please Please,’ she was hysterical. When they pulled out a cape—goodness! James would disappear into the truck, come back out with a different cape, three or four times. When it was obvious he wasn’t coming back out again, that lady lost it. She went right over the wall. When she hit the grass her brand-new shoes fell off. She froze, took one look at the shoes, then one look at the truck and James. It was no contest. She ran after that truck, barefoot.”

James Brown was firmly convinced that that kind of fan, several thousand times over, would pay to have the JB experience on a record. But a live album seemed ludicrous to his label boss Syd Nathan. His label, after all, wasn’t in the album business, nor would a live album produce any singles. Brown paid him no mind—his inspiration, Ray Charles, had already issued two live albums—and booked a remote recording truck to capture one of his live shows at the Apollo Theater from October 19-25, 1962.

Sufficiently warmed up by the 24th—a Wednesday, Amateur Night at the Apollo, when the audience was extra hyped—JB, the Famous Flames and their well-oiled band distilled a raw, brilliantly executed live show onto tape. They found, of course, that Nathan didn’t care. And when the edited show was scheduled for a quiet release the following spring, they heard an album overdubbed with faked screams and applause.

As Brown danced on the rougher edges of African-American music, most commercially successful black artists had “gone pop.” Again, it was Ray Charles who led the way, scoring several heavily orchestrated bits in 1962. At Ben Bart’s urging, Brown attempted to duplicate his success.

JB entered New York’s Bell Sound Studios on December 17, 1962, with master jazz and pop arranger Sammy Lowe to record several well-known ballads: “These Foolish Things,” “Again,” “So Long” and “Prisoner Of Love.” It was Brown’s first multi-track session, and his first recording with strings and a full chorus. Jazz drummer David “Panama” Francis doubled on drums and tympani.

It was an unusually long session. “Prisoner Of Love” took 15 takes, all live with the band. But its final version had the desired effect. By the following spring, “Prisoner Of Love” was James Brown’s first top 20 Pop hit.

The planets were in volatile alignment in 1963. America’s civil rights movement, bubbling since the mid-1950s, burst into focus with the August 28 march on Washington, D.C., one month after Joan Baez and Bob Dylan echoed the voice of the college protestors at the Newport Folk Festival. President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in November startled even the non-political.

Across the tracks, in Oakland, California, Huey P. Newton and others were formulating the Black Panther party. In Detroit, Berry Gordy’s Motown operation was bidding to be “The Sound Of Young America.” Across the Atlantic, groups of post-World War Two baby boomers, spearheaded by The Beatles, were making headlines as creators of the U.K.’s newest sound and image.

James Brown was beginning his ascent into the international consciousness. Simultaneous with “Prisoner Of Love,” his no-bullshit Live At The Apollo quickly became the nation’s second best-selling albums. His touring business, the core of his livelihood, exploded.

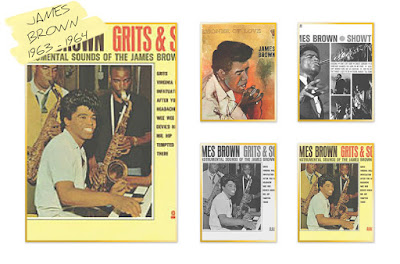

But with Syd Nathan ailing, out of touch with the contemporary music scene yet stubbornly calling the shots, Brown was restless. He formed his own label, Try Me, and song publishing company, Jim Jam Music, under the King umbrella. And then he recorded only three times that year: the original version of “Devil’s Den,” which became his live show theme and the group’s initial foray into the Blue Note/ Prestige school of bluesy funk-jazz; “Oh Baby Don’t You Weep,” a gospel rewrite that became the first of his many two-part singles; and a full-length concert of older material at Baltimore’s Royal Theater. Brown saw King Records, in need of James Brown product, release a live album from the show, Pure Dynamite, but spliced in newer studio material overdubbed with fake applause.

Brown and Bart had broader horizons. They formed the independent Fair Deal Records production company in the fall of 1963, placing JB productions by Anna King and Bobby Byrd with the Smash division of Mercury Records. About the same time, Brown and the band headlined a Motown package tour.

By April 1964 Brown himself appeared on Smash, despite his existing contract with King. During the year he recorded prolifically under the Fair Deal umbrella, producing members of his revue as well as his own big-band revivals of r&b classics; orchestrated arrangements of MOR standards; a gospel-harmony throwback, “Maybe The Last Time”; and an untypical “teen-beat” performance, “Out Of The Blue.”

Referencing once again the advent of commercial jazz, JB recorded several funky instrumentals, including the blue-light special, “Grits.” More profoundly, he cut original compositions that pointed to a new direction: prototype versions of “I Got You” and “It’s A Man’s World,” and a pulsating, jerk dance declaration, “Out Of Sight.”

Brown’s rhythmic core was jump-started by a succession of fresh, inventive players. Joining in 1964 were musical director Nat Jones, and Melvin and Maceo Parker, two cocky teenagers from Kinston, North Carolina.

“James had wanted me to join the year before, but I was still in school, “ Melvin recalled. “The next time he came through town I was ready, and I had Maceo with me. Our bags were packed.

“Somehow, I had the nerve to tell James I wouldn’t go without Maceo. Maceo played tenor, but James needed a baritone – and Maceo carried one of those, too. We were in.”

The Parkers figured they’d stay for a year, then go back to school. Twelve months later, they were drafted into the Army. But they’d both be back, with considerable success.

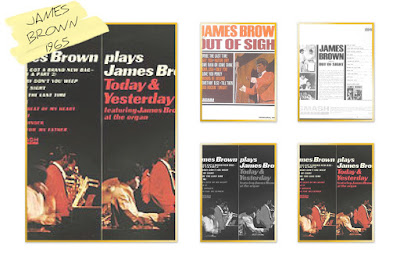

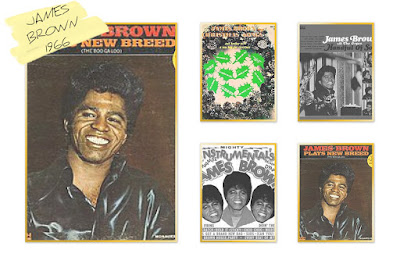

“Out Of Sight” hit the charts just as James Brown’s recording career hit the legal fan. Its success led King to sue Smash, preventing the release Brown’s vocal recordings on Smash, which had to be content with instrumentals and JB productions of other artists. King re-released older albums with new covers.

Mercury Records looked to buy King to get James Brown, but Syd Nathan wouldn’t sell. He wanted his contracted singer back on existing terms. He didn’t, as Brown refused until he got a vastly improved deal.

In late October, 1964, JB and his crew electrified a gaggle of California teenyboppers during the filming of Steve Binder’s T.A.M.I. Show, upstaging the headlining Rolling Stones. Around the same time, Brown, with the Famous Flames, made an extraordinary cameo appearance in the Frankie Avalon movie, “Ski Party.” They lip-synced to the withdrawn Smash version of “I Got You.”

For a moment, anyway, the lack of new product was no problem. James Brown, like his boyhood idol Louis Jordan, was now in movie houses nationwide. More people than ever before could see for themselves that he looked and sounded like no one else in the immediate universe.

Brown, meanwhile, returned to King with a brand new deal—and something from the outer limits in his tape box.

By early 1965, there was a new addition to the JB songbook: “Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag.” Brown based it on a show ad-lib, but in its final form the song not only signaled his new status at King, it articulated a new musical and cultural direction.

In typical JB fashion, “Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag” was recorded in less than an hour on the way to a gig, in February 1965. The band, which included a new member, blues guitarist Jimmy Nolen, was weary from a long bus ride; their exhaustion shows on the original source tape. But fired by pride and their optimistic leader (“This is a Hit!”), they refused to lose the groove.

It was Brown’s first new song for King in more than a year. In a brilliant post-production decision, its exclamatory intro was spliced off and the entire performance was sped up for release. “Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag” went through the roof. Star Time had arrived.

Even the normally self-assured James Brown was astounded at his creation.

“It’s a little beyond me right now,” he told disc jockey Alan Leeds, when the song was new on the charts. “I’m actually fightin’ the future. It’s–it’s–it’s just out there. If you’re thinking, ‘well, maybe this guy is crazy,’ take any record off your stack and put it on your box, even a James Brown record, and you won’t find one that sounds like this one. It’s a new bag, just like I sang.”

Brown followed “Papa’s Got A New Bag” with a freshly minted version of “I Got You,” now subtitled “(I Feel Good).” He went on a roll, appearing on TV programs that had previously shunned him. He built up his “Orchestra,” a combination of jazz and blues players that included new recruits Waymond Reed, Levi Rasbury, Alfred “Pee Wee Ellis,” Clyde Stubblefield, and John “Jabo” Starks. He was also winning awards—and striding into a suddenly open-ended future.

In March 1966, the James Brown caravan crossed the Atlantic for appearances in London and Paris for the first time. On the 11th, they appeared live in an entire episode of “Ready, Steady, Go!,” then Britain’s hippest TV pop music show.

The British “in-crowd” couldn’t cope; presenter Cathy McGowan and her mod acolytes deemed JB to be “simply dreadful.” At the theatre gigs, audience pandemonium proved otherwise. Since then, European fans have provided Brown

a second home across the water.

Back in the U.S., JB was welcomed at Kennedy Airport by hundreds of fans. Within days he headlined a multi-racial bill at Madison Square Garden, and in May debuted in prime time on The Ed Sullivan Show. Brown also hosted a mammoth civil rights rally in Mississippi, and he opened a nodding acquaintance with the Frank Sinatra/ Dean Martin/Sammy Davis Jr. ratpack.

In August 1966, Brown again did what no African-American performer could do: he awarded himself a Lear Jet, with which he flew to the White House to discuss the “Don’t Be A Dropout” campaign with Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey. These were heady times.

Brown’s biggest international hit that year was an impassioned balled, “It’s A Man’s Man’s Man’s World.” Arranged by Sammy Lowe, who worked from a disc dub of the then-unreleased original version, the session featured Lowe’s go-to New York players, a string section, some Brown Orchestra members and a female chorus that was edited out of the final master. Recording went quickly, so quickly that it is barely noted in Lowe’s extensive personal diaries.

“After the first take, James said, ‘That’s it, I like it,’” Lowe said. “He didn’t like to do them over. But I had them take one more, just for safety. Who knows which one they used.”

Brown’s music was expanding, as was his band. The Orchestra was now at its largest, and as Nat Jones helped to interpret Brown’s instructions, there was a distinct shift in its rhythmic mood. Sometimes swing-like ("Bring It Up,” “Ain’t That A Groove”), sometimes simple, hard-driving energy (“Money Won’t Change You”), it wasn’t yet full-blown funk. But it was JAMES BROWN: its own mode, utterly different from Motown, Stax, Atlantic and the other vital musical sources of the era.

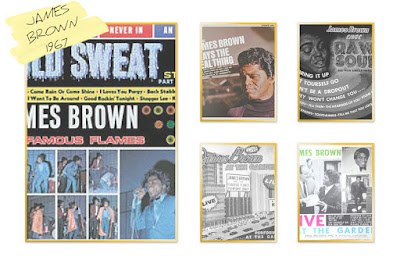

Brown kicked off 1967 like all the preceding years: back on the road. He added a three-piece string section to the Orchestra, which was absolutely unheard of for any working artist at the time, black or white. In mid-January he recorded several shows during a weekend engagement at the Latin Casino nightclub in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, tapes of which were doctored with echo and later released as Live At The Garden.

Despite the strides taken by the entourage, there was momentary trouble. Nat Jones quit the first night of the Casino gig, suffering from mental health problems. Moved up the ranks in his slot was Alfred “Pee Wee” Ellis, who had been handling arrangements for Jones on the side. Ellis was a skilled jazz tenor saxophone player out of Rochester, New York, who had paid little attention to Brown’s career before joining the troupe in February 1966. He caught up fast, however, his first week on the job, at the Howard Theater in Washington, D.C.

“I was flabbergasted, “ said Ellis. “Blown away. I stood there in the wings and I thought, I should have bought a ticket. It was that much of a privilege to be that close to James Brown and that band.”

By the second night of the Latin Casino engagement, he and Brown had worked up “Let Yourself Go,” a song that musically signaled changes taking place. Brown still called the shots—after a few takes he replaced drummer Stubblefield with Starks, then stopped the recording to suggest a last-minute ad-lib—but the band was developing into an unrivaled powerhouse.

No one really noticed the new brew until the summer, when the mind-blowing single “Cold Sweat” blasted through the hot air.

It was just rhythm—barely any chord changes—with jazz intervals in the horn section inspired by Miles Davis’ “So What.” It contained another first—a “give the drummer some” solo by Clyde Stubblefield. And Brown shaped it in the studio in only two takes.

“’Cold Sweat’ deeply affected the musicians I knew,” said Jerry Wexler, who was then producing Aretha Franklin and other soul stars for Atlantic Records. “It just freaked them out. For a time, no one could get a handle on what to do next.”

James Brown kept going. He made his Tonight Show debut and recorded a set at the Apollo Theater in late June for future release. His next single was “Get It Together,” a monstrous two-parter in which JB gave each band member “some.” And Brown’s sign-off at the end—“fade me on outta here ’cause I got to leave anyway”—wasn’t just an ad-libbed cue for the engineer. He literally rushed out the door to set up advance promotion for the next night’s gig in Richmond, Virginia.

“So many things that were done weren’t written, because you just couldn’t,” “Jabo” Starks has said. “You couldn’t write that feel. Many, many times we’d just play off each other, until James would say, ‘That’s it!’”

Throughout this transitional year, James Brown had more than just a unique sound and road show. While there were further recordings with Sammy Lowe and, for the first time, with the Dapps, a white group from Cincinnati, Brown was also emerging as a spokesman and role model.

JB struggled with his role. Patriotically, he accepted an appointment to co-chair a Youth Opportunity Program with heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali. He found it swiftly canceled when Ali refused the military draft.

Yet in the face of modern soul music, embodied by Aretha Franklin and the Stax Records label, strutting into the mainstream, and Stax’s Otis Redding being embraced by the acid-rock generation at the Monterey Pop Festival, Brown moved to embrace the Las Vegas market, performing such supper-club standards as “That’s Life” and “I Wanna Be Around,” even as “Cold Sweat” was turning heads.

Then, in 1968, Brown lost his dream weavers: the boss Syd Nathan, a respected adversary; singer Little Willie John, a deeply personal inspiration; Ben Bart, his business mentor and father figure; and the whole of King Records, sold twice in two months.

But JB’s personal troubles dimmed beside other tragedies. Assassins’ bullets felled Martin Luther King, Jr. and Presidential candidate Robert Kennedy in a two-month span, adding heat and rage to an already-smoldering African-American nation. The Vietnam War ramped up as nationwide protests gained steam.

Brown stepped to the fore. The day after King’s assassination, he was televised in concert at the Boston Garden to calm the rioting. He was flown to Washington, D.C. to speak on the radio and urge brotherhood. Brown and his wife were also invited to a White House dinner with President Johnson.

During the same year Brown bought his first two radio stations, WJBE in Knoxville, Tennessee, and WRDW in Augusta, Georgia. He entertained on the African Ivory Coast and for the U.S. Troops in Vietnam; collected innumerable citations; and wound up the year touring with the Count Basie Orchestra as his support act.

James Brown was proving to be a man of considerable influence. But gestures to the U.S. government didn’t endear him to black militants. To them, Soul Brother No. 1 was siding with “The Man.” James Brown felt he was doing no such thing. He was reacting to individual situations with no sophisticated philosophy except advancement for himself—and, by example, the African-American nation.

After all, he could reason, wasn’t the presence of a seventh-grade dropout from South Carolina at the White House dinner table enough of a message?

Brown instead focused his musical message. The new tunes were powerful, if lyrically ambiguous: “I Got The Feelin’” and “Licking Stick-Licking Stick,” the latter recorded just a few days after King’s death. But by the summer of riots, JB recorded his most profound anthem, “Say It Loud – I’m Black And I’m Proud.”

It’s not clear whether Brown bowed to militant pressures to record it, or whether he simply thought it was time. Whatever the source, JB listened. In fact, between takes, he stage-whispered to everyone present, “About 50 million people waitin’ to hear this one.”

The entourage felt a sense of urgency throughout the rest of the 1960s. Led by Ellis, the band sharpened under constant rehearsals; the final touches engineered by a supremely confident JB. “Hit me!” he cried, and they did, like no one else.

“Man, we used to cut, like Sherman tanks coming down the aisles, “ said drummer Clyde Stubblefield of Chattanooga, Tennessee, remembering what it was like to be in the eye of the hurricane. “One time, at Soldier’s Field in Chicago, we were on the grass with little Vox PA systems—no monitors. I looked way up at the top and I tried to figure out, ‘How are they going to hear us?’ But they were up there rockin’!”

Of course, with such a punishing schedule the band wasn’t always tight like that. They literally paid for their mistakes, as Brown would fine them for bum notes or a dull finish on their shoes. JB, however, through subtle gestures or an ad-libbed phrase, could make even the worst mistakes work on the fly.

His No. 1 hit “Give It Up Or Turnit A Loose” offers two examples: during the intro the horns offer a weak riff to JB’s cue; he says, right on the finished record, “start it over again.” When Charles Sherrell, the bass player, walks up to the bridge of the tune a bit early, Brown doesn’t stop the song, he intercepts and corrects the error with a rhythmic cascade of “no-no-no-no-no’s.” Other times, Maceo was called upon to solo—“Maceo, I want you to blow”—when JB himself ran out of rhymes. And every drummer new or old trained their eyes on the back of the boss’ head and shoulders, ready for a body cue to pop the snare.

It was why Fred Wesley would say later, “The first rule when you went to work for James Brown: watch James Brown.”

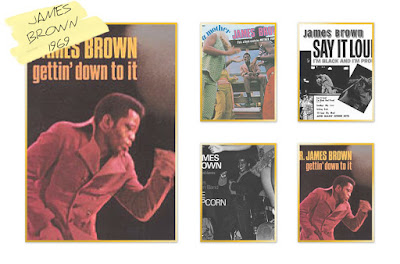

Soul Brother No. 1 began 1969 on a furious roll. His funk and the message got heavier: “I Don’t Want Nobody To Give Me Nothing,” a personal anthem, preceded a slew of “Popcorn” records. They pumped up the stage show, while Brown continued to court the mainstream. He recorded cocktail instrumentals with Cincinnati’s Dee Felice Trio, and appeared for an entire week on The Mike Douglas Show in June, performing with Felice as well as his regular ensemble.

Yet Brown was in danger of being upstaged. He found serious competition from funk-rock bands, among them Sly & the Family Stone and the revamped Isley Brothers, as well as Motown’s Norman Whitfield productions. To top it off, a few key players in the JB Orchestra had left.

In March 1970, Brown suffered another blow: the guts of the 1960s band, including Maceo and Melvin Parker, Jimmy Nolen and Alofonzo “Country” Kellum, walked out, leaving only Byrd, who had recently returned with vocalist Vicki Anderson from an 18-month stab at independence, and Starks, an old-school loyalist.

Enter the Pacesetters, a band of eight Cincinnati teenagers who leaped suddenly from King studio fill-ins to Soul Brother No. 1’s swaggering front-liners. Prominent among them were the Collins brothers, William, a.k.a. “Bootsy” on bass, and Phelps, a.k.a. “Catfish” on rhythm guitar.

“James Brown and his band were our heroes,” said Bootsy. “We knew all the tunes, but we couldn’t imagine actually playing with them. I mean, one night with a guy like Jabo would have been it. To tell the truth, I don’t think I ever got used to the fact that I was there.”

Brown’s “New Breed”—their name before he settled on The J.B.’s—had a profound effect on his sound, stance and future. Through them Brown shifted emphasis from the horns to guitar, taking the whole of African-American music with him. The J.B.’s got JB back to basics.

Their catalog, in just eleven months together: “Sex Machine,” “Super Bad,” classic remakes of “Sex Machine” and “Give It Up Or Turnit A Loose,” “Talking Loud & Sayin’ Nothing,” “Get Up, Get Into It And Get Involved,” and “Soul Power.” Staggering. They defined a new order.

Brown kept his momentum, but he was also in a tenuous position. Another desertion would have left him with no support. In response, Brown lightened his discipline to give the J.B.’s room to grow—and he respected their budding talent.

“James never went off on us,” “Catfish” said. “He never fined us, like he did with Maceo and those guys. We just got the job done.”

The original session tape of “Super Bad” reveals Brown acting the encouraging teacher as well the exacting leader.

“That’s hell of a groove, fellas,” Brown exclaimed after the song’s first run-through, but he grew testy with questions about the song’s intro.

“Do anything you wanna, man,” he snapped. “Don’t bug me. OK? Just play what you play. Don’t be a drag.”

By the next attempt, however, Brown was thoroughly pleased, and he was careful to reassure his new crew. “Play as hard as you want, I don’t care, ’cause you know where you’re going now. Just go for yourself. You’re doing fine.”

Brown also undermined the group’s spirit. On the road he substituted local musicians for the young horn players. And once his Orchestra veterans—saxophonist St. Clair Pinckney, drummer Clyde Stubblefield and trombonist Fred Wesley—returned to the fold, the J.B.’s Mark I band looked elsewhere. Following a tension-filled gig at New York’s Copacabana, Bootsy and Catfish said “See Ya,” and eventually hitched a ride on George Clinton’s P-Funk Mothership.

James Brown grooved on with the new J.B.’s, directed by the Alabama-born, jazz-bred Wesley.

“They were totally green,” Wesley said. “[Hearlon] ‘Cheese’ Martin was so used to playing rhythm, just scratching behind James, that I had to teach him to play lead guitar. And at first Fred Thomas wasn’t much of a bass player. We rehearsed for two weeks in the basement of the Apollo Theater just to get the show together.”

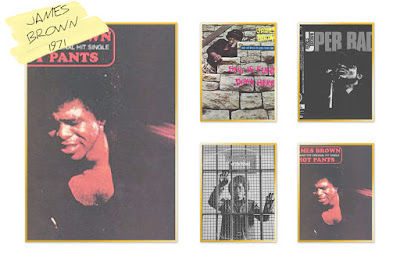

Within two months they had recorded the hits “Escape-ism,” Bobby Byrd’s “I Know You Got Soul” and “Hot Pants.” Brown placed each with his new label, People. It was his last fling with King Records, now owned by Lin Broadcasting and soon to be purchased by the Tennessee Recording and Publishing Co.

But the TRPC ended up with little: on July 1, 1971, Brown, and his extensive, lucrative back catalog, signed to Polydor Records, which had been distributing him internationally since January 1968.

Polydor was a firmly established international music corporation that at the time had a relatively low profile in the U.S. They got their major shot of street credibility via the main man. In return James Brown received more money, artistic freedom and stronger international representation, not to mention his own office and promotion team at Polydor’s New York headquarters on Seventh Avenue. The company also picked up the People label, offering Brown an outlet for releases from the J.B.’s, Lyn Collins, a returning Maceo Parker and other JB productions.

To kick off his signing, Brown cancelled the already-mastered King album, Love Power Peace, a triple-LP set recorded live in Paris during the final days of the first J.B.’s. To substitute, he recorded in July alone a brand-new live album, Revolution Of The Mind: Live at the Apollo Vol. III, plus a new version of “Hot Pants” and the single “Make It Funky.”

It was a prolific time. From the summer of 1971 through the winter of ’72, Brown scored 10 top ten R&B/Soul chart hits in a row, against a backdrop of new music from Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, the Isley Brothers, Al Green, the Philadelphia International label, and a new generation of funk groups. Approaching 40, he transformed from an aging “Soul Brother No. 1” into a venerated “Godfather of Soul.”

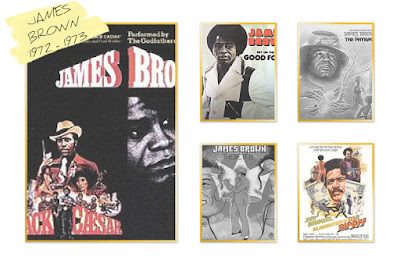

Brown faltered briefly in 1973, crushed by grief. Teddy, his oldest son, died in a car accident in June. JB pressed on. He scored two films, Black Caesar and its sequel, Slaughter’s Big Rip-Off. He was to record a third soundtrack, centered around a stinging track “The Payback,” but the film’s producer rejected it, and JB retained it as the title track for his own double-LP.

Brown again looked to play funk and (what he saw as) more sophisticated arrangements, working with Dave Matthews, an ex-symphony player from Cincinnati, as a contemporary replacement for Sammy Lowe. JB often preferred to his own band Matthews’ favorite New York session players, who included the cream of the new fusion stars, among them David Sanborn, Joe Farrell, Billy Cobham and Hugh McCracken. Their collaboration produced the potent hits “King Heroin”—featuring a spoken word rap written by ex-con Manny Rosen, who waited tables at Brown’s favorite New York deli hangout—“Public Enemy #1” and “I Got A Bag Of My Own,” a fresh re-write of “Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag.”

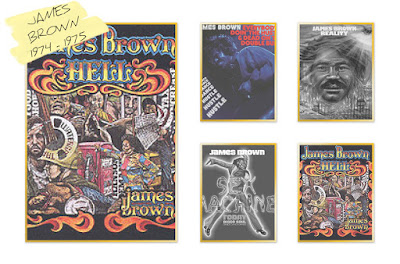

At this time James Brown, bolstered by Polydor’s marketing might, became an album seller. Hot Pants, Revolution Of The Mind, There It Is, Get On The Good Foot, the two film soundtracks, and 1974’s two-record sets, The Payback and Hell, proved he was still in the vanguard.

But even James Brown had no guarantees the hits would continue. In 1975, after the single “Funky President,” from the album Reality, had run its course, Brown saw the end of a historic commercial streak.

IV: I REFUSE TO LOSE

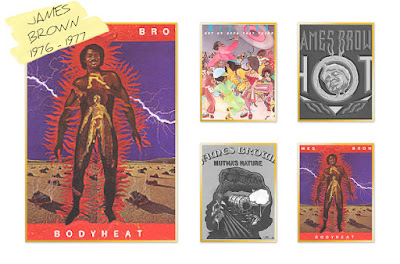

By the mid-seventies James Brown was caught between two musical trends: too raw for disco, not heavy or freaky enough for the Parliament-Funkadelic crowd.

Brown himself was showing signs of weariness and insecurity. He’d been breaking his back for 20 years, running the whole show. Most men attempting half as much would have dropped dead years past. He was the most successful African-American musician of the 20th Century, an internationally renowned superstar—but he hadn’t yet been given establishment respect at home.

Brown witnessed acts that he’d inspired break through with more publicity, bigger advances and far greater opportunities than he’d ever enjoyed. His relationship with Polydor soured. Troubles with the IRS began.

His personal problems were reflected in his recordings; Brown started following trends instead of leading them. Despite his troubles, Brown could serve up such hard-hitters as “Get Up Offa That Thing” and “Body Heat,” both international hits in 1976-77.

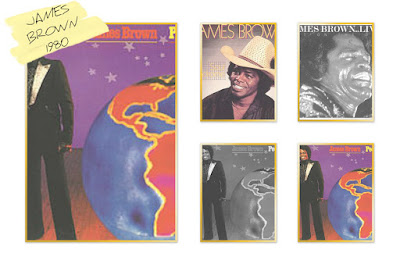

In 1979, after years of producing his own records, JB reluctantly agreed to work with an outside producer, Brad Shapiro. He knew that Shapiro had produced several best sellers for Sam & Dave, Wilson Pickett and Millie Jackson. Their collaboration, which produced the album The Original Disco Man and its single, “It’s Too Funky In Here,” were moderately successful, enough to call it a comeback.

Shapiro, a Brown fan since he had seen him perform in 1961, had been tutored in the studio by Henry Stone and was fully aware of his idol’s temperamental ego. He maintained complete control of the sessions—a monumental concession for the fiercely independent James Brown—yet he found himself in awe at Brown’s energy and creativity.

“I was mesmerized by his raw sense of rhythm,” Shapiro said. “When we cut ‘It’s Too Funky In Here’ he just grabbed the microphone, whirled around and hit that line, ‘I need a little air freshener under the drums’—and man, I just got out of his way!”

“It’s Too Funky In Here” became a favorite of Brown’s occasional live shows. He toured Great Britain and Europe more frequently than the States, and in December 1979 played to adoring crowds in Tokyo, Japan. Brown’s Tokyo shows were released as Hot On The One, a double-live album, one of his last for Polydor.

In 1980, riding out his Polydor contract, Brown recorded “Rapp Payback (Where Iz Moses),” a dynamic update of his classic trance-like single. He released it on TK Records, a disco-oriented label that had successfully challenged JB’s chart authority in the mid-70s. TK was run by Henry Stone.

X: LIKE IT IS, LIKE IT WAS

Mr. James Brown saw a rebirth in the 1980s. Following a brief fling with the new wave clubs that had rediscovered him, Brown was introduced to a broader pop audience via films in which the principal creative forces were James Brown fans: The Blues Brothers, featuring Brown as a rousing preaching opposite John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd; Doctor Detroit, also with Aykroyd; and Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky IV, which showcased JB in a mythic cameo performing “Living In America,” his biggest Pop hit since 1968’s “Say It Loud – I’m Black And I’m Proud.”

The night “Living In America” reached the U.S. Top Five, James Brown was inducted as a charter member into the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall Of Fame. He had gained the establishment recognition he craved. And he was the only inductee to have a contemporaneous hit.

At street level, a fundamentally more important appreciation of James Brown was taking place. An entire new generation was discovering his music and recycling, through sampling, his legacy as the soundtrack for their own aspirations. “Funky Drummer,” a nearly forgotten 1970 single-only release, was in particular an irresistible foundation for material. Aficionados estimate that between two and three thousand recorded raps of the late 1980s featured a James Brown sample in some form. In addition, his recordings with Afrika Bambaataa (“Unity”) and Brooklyn’s Full Force (“Static,” “I’m Real”) were homages paid by respectful disciples.

In December 1988, James Brown was handed two concurrent six-year prison sentences, on traffic violations charges and resisting arrest. As part of his sentence, the Godfather of Soul dutifully counseled local poor and preached against drugs. He was freed on February 27, 1991.

While Brown was off the scene, his old label Polydor cashed in. “She’s The One,” an unreleased track recorded in 1969, became a mild hit in the U.K. Brown’s legacy, Polydor discovered, had staying power: a follow-up single, “The Payback Mix – Part One,” a dynamite megamix by Coldcut, did even better, peaking at No. 12 on the U.K. pop charts.

After Brown’s release from prison, he performed for a pay-per-view event, then resumed recording, first for Scotti Brothers and later for several small labels including his own Georgia-Lina Records. Brown found the recording business changed dramatically during the 50 years he had spent in studios. The irony was that while Brown’s old beats and riffs were sampled and heard more widely than ever, his own new records struggled for attention. He won a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1992, at the same ceremony in which he shared a Grammy for Best Album Notes, awarded to his career-defining box set, Star Time.

Though he hungered for a hit again like “Living In America,” an iconic performer like James Brown no longer needed hit records to sell tickets; throughout the 1990s and 2000s he was a bona fide headliner, often appearing in the world’s most prestigious venues.

James Brown died on Christmas morning, 2006, after a brief illness. Remarkably, at the time of his unexpected death his touring business was more profitable than at any point in his career. Throughout his lengthy career Brown laid claim to many appropriate nicknames including “Mr. Dynamite” and “The Hardest Working Man In Show Business” but just one is an apt legacy. Long live James Brown – THE GODFATHER OF SOUL.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire